Debating FEMA’s future as storms, floods worsen / July 18, 2025 / NJ Spotlight

By Brenda Flanagan

Monday’s flash floods reminded New Jersey residents just how quickly flash floods can strike — and what role the Federal Emergency Management Agency can play in their recovery and resilience.

It brought back bad memories for towns like Highlands Borough in Monmouth County, where torrential rains rose rapidly eight years ago and inundated the coastal town. Flash floods continue to swamp Route 36, said Highlands Mayor Carolyn Broullon.

“Oftentimes it completely closes State Highway 36, which is an evacuation route, so it’s dangerous,” she said. “People would be trapped in their homes with no way out, and their cars would be, you know, water over the dashboard.”

To keep its downtown dry and its residents safe, Highlands had applied for a special $13 million FEMA flood resilience grant to renovate Kavookjian Field with an underground detention basin that would store floodwaters and a pumping station to clear the grounds.

It won all preliminary permits, but this April, FEMA informed the borough that it killed the entire program, leaving Broullon “…to use a British term, gutted. Absolutely gutted. We were so excited to finally fix this century-long issue and to have it just pulled out from under us, is very trying,” she said.

The elimination of the resiliency funding is part of the Trump administration’s dramatic shift in focus for the agency, even as extreme weather and natural disasters grip wide swaths of the country, including flash flooding in Central Texas that left more than 120 dead.

A FEMA spokesman called its flood protection grants “wasteful and ineffective … more concerned with climate change than helping Americans effected (sic) by natural disasters.”

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem has defended the cuts and said on CBS’ “Meet the Press:” “The President recognizes that FEMA should not exist the way it always has been. It needs to be redeployed in a new way.”

For one, any FEMA contract over $100,000 now now requires Noem’s personal sign-off.

“And I can’t think of a worse idea to do right now on the heels of a major storm in our state,” said state Attorney General Matt Platkin, who this week a coalition of 20 states that sued the Trump administration over its cuts, including those in Highland.

“The president in this country has broad powers, but he’s not a king,” Platkin said. “He does not have the ability or the legal right to withhold funds that Congress in a bipartisan way, came together and said these funds need to be spent to do certain things. In this case, these funds need to be spent to protect us from floods, natural disasters, wildfires.”

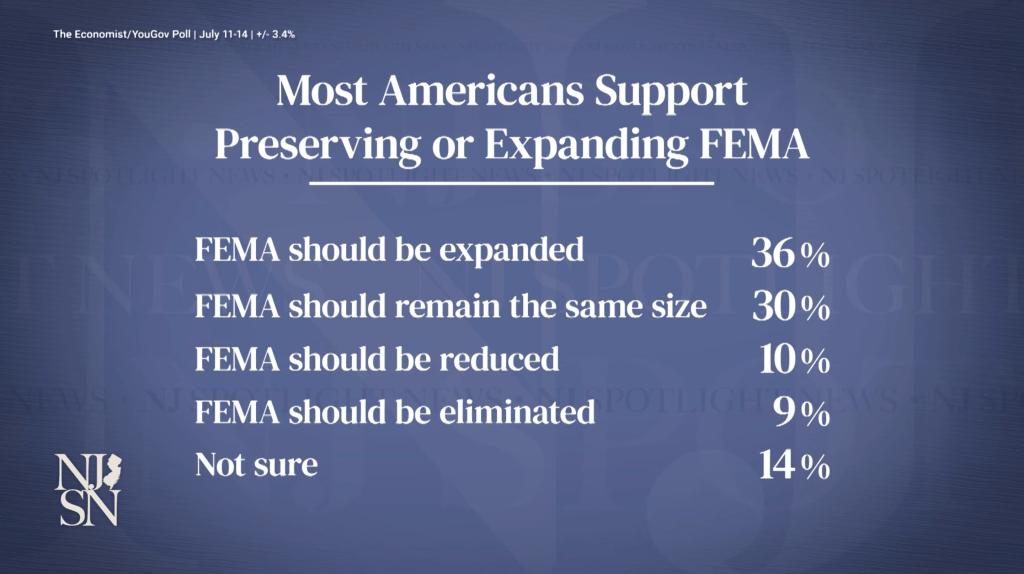

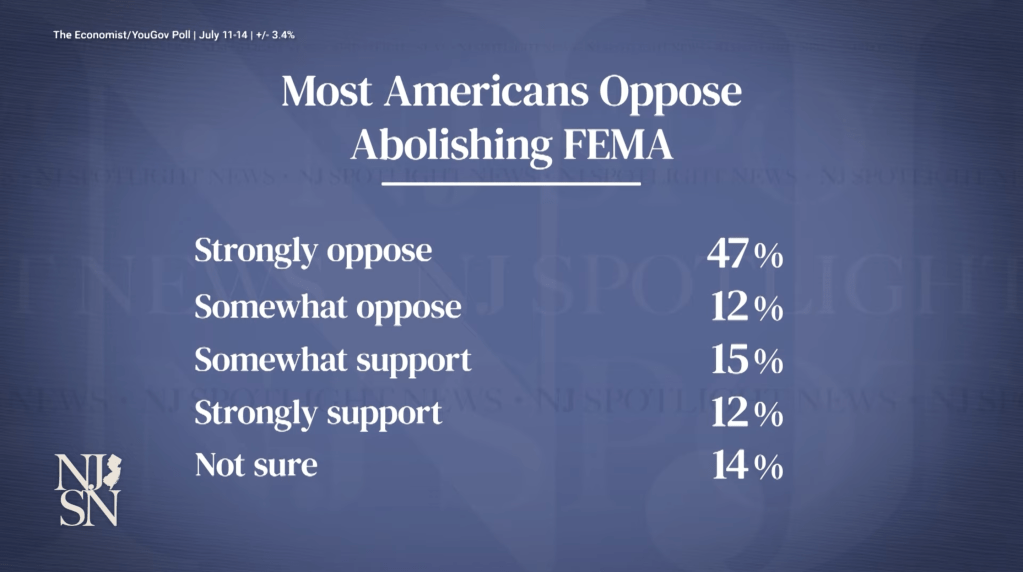

A new poll by The Economist/YouGov found a large majority of Americans don’t want FEMA cut back, and 36% want it expanded. Nearly 60% opposed abolishing FEMA altogether, versus 27% who supported the move.

“We believe we should be very concerned about what’s going on with FEMA at the federal level,” said Amanda Devecka-Rinear, co-founder of New Jersey’s Organizing Project after Superstorm Sandy.

As a storm survivor and advocate, Devecka-Rinear said she would love to see FEMA reformed so the problem-plagued agency could respond faster, with fewer denials and better survivor support. But following Monday’s storms, Devecka-Rinear warned residents about FEMA’s response.

“If that doesn’t reach the level of federally declared disasters, we have nothing to support those people in the state of New Jersey,” she said, adding the state might have to provide its own emergency relief.

The Murphy administration had no comment on the prospect of a new state program, and spokesperson Tyler Jones praised FEMA’s contributions: “The success of our state’s emergency response and recovery efforts has been made possible through the strong and sustained support of our federal partners at FEMA.”

“Simply put, New Jersey would not be as ready or as resilient today without FEMA’s ongoing partnership,” she said.

Meanwhile, in Highlands, the mayor is looking for other funding sources for flood prevention projects that don’t rely on federal approval.

“We’re feisty here in Highlands,” Broullon said. “We can find ways of doing things. You have to become used to it because — until we have a fix — you always have to have a plan.”